Learning (some) Hebrew can greatly benefit Christians by providing a deeper understanding of the origins, culture, and texts that form the foundation of our faith.

Most likely, Jesus spoke Aramaic as his primary language, as it was the common language spoken in the region of Palestine during the 1st century. A Semitic language, it is closely related to Hebrew and remains in use nowadays by Christian and Jewish communities in Iraq, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and even in Russia. Since it was the language used in everyday conversations, trade, and community interactions in Jesus’ day and age, historians assume that he grew up speaking Aramaic within his family and community.

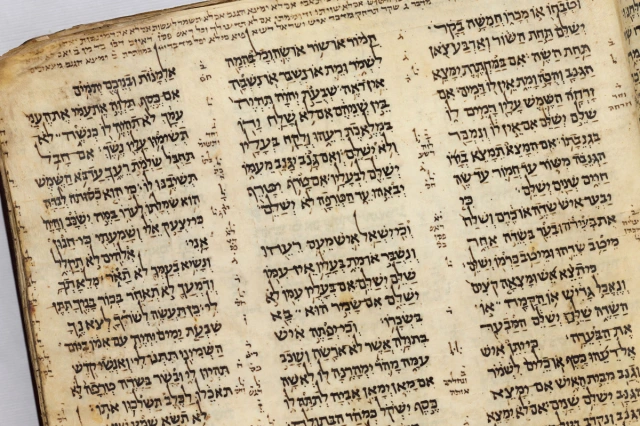

However, it is also probable that Jesus had some knowledge of Hebrew. Hebrew was the language of religious texts and rituals, and Jesus, being raised in a devout Jewish family, would have been familiar with Hebrew Scriptures and participated in Hebrew religious practices.

Furthermore, due to the Roman occupation of the region, it is plausible that Jesus had some exposure to Greek. Greek was the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean and was commonly used for commercial and administrative purposes. The influence of Greek culture and language during that time means that Jesus and his disciples would have met Greek speakers – and it is conceivable that they themselves had some ability to communicate in Greek. The Gospels, in fact, are all written in Greek.

While Aramaic was likely Jesus’ primary language, his familiarity with Hebrew and potential exposure to Greek would have provided him with a broader linguistic context, allowing him to engage with various individuals and communities during his ministry. That is one of the reasons why learning Hebrew can greatly benefit Christians by providing a deeper understanding of the origins, culture, and texts that form the foundation of their faith. Hebrew is the language in which significant portions of the Old Testament were written, and it carries unique linguistic nuances and theological insights that are sometimes lost in translation. By growing familiar with (at least some) Hebrew words and concepts, Christians can gain a more profound appreciation for the biblical narratives, theological themes, and historical context that shape their beliefs. Here are three important Hebrew words every Christian should know:

Elohim – The Hebrew word Elohim is frequently translated as “God” (or “Gods”) in the Bible. That is, to a certain extent, correct. The word Elohim is the plural for Eloah. In some passages of the Bible, Elohim refers to the singular gods of other nations, or to deities in the plural. But in some others, it is one of the primary names for God – and that is how it is mostly used throughout the Hebrew Bible. Calling God Elohim conveys the idea of His supreme authority, power, and sovereignty.

Ruach HaKodesh – The Hebrew phrase Ruach HaKodeshtranslates as Holy Spirit. In both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, the Ruach HaKodesh always refers, unequivocally, to the Spirit of God. The expression refers to the presence and power of God in the world and in the lives of believers – associated with divine inspiration, revelation, guidance, transformation, and empowerment for spiritual service.

Kippur – This Hebrew word refers to the concept of atonement. Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest day of the year for Jews. It is a time of fasting, prayer, and repentance, where individuals seek forgiveness for their sins and reconcile with God. Although some authors understand forgiveness and atonement to be radically different, it is true that they both highlight the human (and divine) capacity of victims and creditors to forgive transgressors and debtors from both moral and financial debts. This understanding of debt release is found in Deuteronomy 15 (the famous Remissionis Domini, the Shmita, the Jubilee) and is echoed in the Greek original formulation of the Lord’s Prayer (“forgive us our debts,” kae aphes hēmin ta opheilēmata hēmōn) and in Jesus’ first sermon as found in the gospel of Luke, which presents him unrolling the scroll of Isaiah on a Saturday in the synagogue, and announcing he had come to proclaim “the Year of the Lord,” the Jubilee Year.

By learning these Hebrew words and their meanings, Christians can gain deeper insights into the Scriptures, the character of God, and the historical and cultural context of their faith. Exploring some of these linguistic nuances opens avenues for studying the Bible more comprehensively, and enables a more profound connection